University Of The Witwatersrand Wiki, The University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, is a multi-campus South African public research university[4] situated in the northern areas of central Johannesburg. It is more commonly known as Wits University or Wits (/vəts/ or /vɪts/). The university has its roots in the mining industry, as do Johannesburg and the Witwatersrand in general. Founded in 1896 as the South African School of Mines in Kimberley,[2] it is the third oldest South African university in continuous operation, after the University of Cape Town (founded in 1829),[5] and Stellenbosch University (founded in 1866).[6]

In 1959, the Extension of University Education Act forced restricted registrations of black students for most of the apartheid era; despite this, several notable black leaders graduated from the university. It was desegregated once again, prior to the abolition of apartheid, in 1990. Several of apartheid’s most provocative critics, of either European or African descent, were one-time students and graduates of the university.[1]

The university has an enrolment of 38,353 students as of 2017, of which approximately 20 percent live on campus in the university’s 22 residences. 65 percent of the university’s total enrolment is for undergraduate study, with the remaining 35 percent being postgraduate.[7]

Contents

- 1History

- 1.1Early years: 1896–1922

- 1.2Open years: 1922–1959

- 1.3Growth and opposition to apartheid: 1959–1994

- 1.4Post-apartheid: 1994–present

- 1.5Coat of arms

- 2Governance and administration

- 3Campuses

- 4Sites

- 4.1Provincial heritage sites and heritage objects

- 4.2Wits Institute of Social and Economic Research (WiSER)

- 4.3Cradle of Humankind

- 4.4Museums

- 4.5Rock art

- 4.6Johannesburg Planetarium

- 4.7Wits Art Museum

- 4.8Wits Theatre

- 5Academics

- 5.1Research

- 5.2Faculties

- 5.2.1Commerce, Law, and Management

- 5.2.2Engineering and the Built Environment

- 5.2.3Health Sciences

- 5.2.4Humanities

- 5.2.5Science

- 5.3Libraries

- 5.4Reputation and ranking

- 6Frankenwald controversy

- 7Student demographics

- 7.1Racial composition

- 7.2Gender composition

- 8Notable alumni and academics

- 8.1Nobel Prize Laureates

- 9See also

- 10References

- 11Bibliography

- 12External links

History[edit]

The Great Hall, on East Campus, where graduation ceremonies, ceremonial lectures, concerts and other functions are held.

East Campus as seen from the north of the campus. Solomon Mahlangu House and the high-rise buildings of Braamfontein are visible in the background.

Early years: 1896–1922[edit]

The university was founded in Kimberley in 1896 as the South African School of Mines. Eight years later, in 1904, the school was moved to Johannesburg and renamed the Transvaal Technical Institute. The school’s name changed yet again in 1906 to Transvaal University College. In 1908, a new campus of the Transvaal University College was established in Pretoria. The Johannesburg and Pretoria campuses separated on 17 May 1910, each becoming a separate institution. The Johannesburg campus was reincorporated as the South African School of Mines and Technology, while the Pretoria campus remained the Transvaal University College until 1930 when it became the University of Pretoria.[1][8] In 1920, the school was renamed the University College, Johannesburg.[1]

Open years: 1922–1959[edit]

Finally, on 1 March 1922, the University College, Johannesburg, was granted full university status after being incorporated as the University of the Witwatersrand.[9] The Johannesburg municipality donated a site in Milner Park, north-west of Braamfontein, to the new institution as its campusand construction began the same year, on 4 October. The first Chancellor of the new university was Prince Arthur of Connaught and the first Principal (a position that would be merged with that of Vice-Chancellor in 1948)[10] was Professor Jan Hofmeyr.[11] Hofmeyr set the tone of the university’s subsequent opposition to apartheid when, during his inaugural address as Principal he declared, while discussing the nature of a university and its desired function in a democracy, that universities “should know no distinctions of class, wealth, race or creed”.[12] True to Hofmeyr’s words, from the outset Wits was an open university with a policy of non-discrimination on racial or any other grounds.[1]

Initially, there were six faculties—Arts, Science, Medicine, Engineering, Law and Commerce—37 departments, 73 academic staff, and approximately 1,000 students.[13] In 1923, the university began moving into the new campus, slowly vacating its former premises on Ellof Street for the first completed building in Milner Park: the Botany and Zoology Block. In 1925, the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VIII) officially opened Central Block (which includes the Great Hall).[1]

The university’s first library, housed at the time in what was meant to be a temporary construction, was destroyed in a fire on Christmas Eve in 1931. Following this, an appeal was made to the public for ₤80,000 to pay for the construction of a new library, and the acquisition of books. This resulted in the fairly rapid construction of the William Cullen Library; completed in 1935.[14] During this period, as the Great Depression hit South Africa, the university was faced with severe financial restrictions. Nonetheless, it continued to grow at an impressive rate. From a total enrolment of 2,544 students in 1939, the university grew to 3,100 in 1945. This growth led to accommodation problems, which were temporarily resolved by the construction of wood and galvanised-iron huts in the centre of the campus (which remained in use until 1972).[1]

During World War II, Wits was involved in South Africa’s war efforts. The Bernard Price Institute of Geophysical Research was placed under the Union of South Africa’s defence ministry, and was involved in important research into the use of radar. Additionally, an elite force of female soldiers was trained on the university’s campus.[14]

In 1948 the National Party (NP) was voted into power by South Africa’s white electorate on a platform of “apartheid” (Afrikaans for “separateness”). The NP’s aim was to create an artificial white majority in most of South Africa by depriving the black majority of their citizenship, making them citizens of the “homelands” associated with their ethnic groups instead. These were, in theory, “self-governing”, and in four cases were later granted “independence”. But in reality, their lack of economic infrastructure left even the supposedly independent homelands as little more than South African puppet states. This policy of “grand apartheid” was accompanied by the extension of racially discriminatory measures within so-called “white South Africa”, including the segregation of universities. Wits initially managed to remain an open institution, but by 1956 the NP government began to seriously push for the full implementation of university apartheid.[15] In response, in 1957, Wits, the University of Cape Town, Rhodes University and the University of Natal issued a joint statement entitled “The Open Universities in South Africa”, committing themselves to the principles of university autonomy and academic freedom.[15]

In 1959, the apartheid government passed the Extension of University Education Act, which achieved the enforcement of university apartheid. Wits protested strongly and continued to maintain a firm and consistent stand in opposition to apartheid. This marked the beginning of a period of conflict with the apartheid regime, which also coincided with a period of massive growth for the university.[1]

Growth and opposition to apartheid: 1959–1994[edit]

West Campus, formerly the Milner Park showgrounds, was acquired by Wits in 1984.

The Gavin Reilly Green on West Campus.

As the university continued to grow (from a mere 6,275 students in 1963, to 10,600 in 1975, to over 16,400 by 1985), the expansion of the university’s campus became imperative. In 1964, the medical library and administrative offices of the Faculty of Medicine moved to Esselen Street, in the Hillbrow district of Johannesburg. In 1968, the Graduate School of Business was opened in Parktown. A year later, the Ernest Oppenheimer Hall of Residence and Savernake, the new residence of the Vice-Chancellor (replacing Hofmeyr House on the main campus) were both established, also in Parktown. That same year, the Medical School’s new clinical departments were opened.[1]

During the course of the 1960s, Wits acquired a limestone cave renowned for its archaeological material located at Sterkfontein. A farm next to Sterkfontein named Swartkrans rich in archaeological material was purchased in 1968, and excavation rights were obtained for archaeological and palaeontological purposes at Makapansgat, located in Limpopo Province.[1]

The 1960s also witnessed widespread protest against apartheid policies. This resulted in numerous police invasions of campus to break up peaceful protests, as well as the banning, deportation and detention of many students and staff. Government funding for the university was cut, with funds originally meant for Wits often being channelled to the more conservative Afrikaans universities instead. Nonetheless, in the words of Clive Chipkin, the “university environment was filled with deep contradictions”, and the university community was by no means wholly united in opposition to apartheid. This stemmed from the Wits Council being dominated by “highly conservative members representing mining and financial interests”, and was compounded by the fact that the mining industry provided major financial support for the university. With a strongly entrenched “[c]olonial mentality” at Wits, along with “high capitalism, the new liberalism and communism of a South African kind, combined with entrenched white settler mores (particularly in the Engineering and Science faculties) … the university … was an arena of conflicting positions generally contained within polite academic conventions”.[16]

| “ | The University of the Witwatersrand is dedicated to the acquisition, advancement and imparting of knowledge through the pursuit of truth in free and open debate, in the undertaking of research, in scholarly discourse and in balanced, dispassionate teaching. We reject any external interference designed to diminish our freedom to attain these ends. We record our solemn protest against the intention of the Government, through the threat of financial sanctions, to force the University to become the agent of Government policy in disciplining its members. We protest against the invasion of the legitimate authority of the University. We protest against the proposed stifling of legitimate dissent. In the interests of all in this land, and in the knowledge of the justice of our cause, we dedicate ourselves to unremitting opposition to these intended restraints and to the restoration of our autonomy. | ” |

| — Plaque unveiled at the Wits General Assembly of 28 October 1987[15] | ||

The 1970s saw the construction of Jubilee Hall and the Wartenweiler Library, as well as the opening of the Tandem Accelerator; the first, and to date only, nuclear facility at a South African university.[14] In 1976, Lawson’s Corner in Braamfontein was acquired and renamed University Corner. Senate House, the university’s main administrative building, was completed in 1977. The university underwent a significant expansion programme in the 1980s. The Medical School was moved to new premises on York Street in Parktown on 30 August 1982. Additionally, in 1984 the University acquired the Milner Park showgrounds from the Witwatersrand Agricultural Society. These became West Campus,[16] with the original campus becoming East Campus.[1]In 1984, the Chamber of Mines building opened. A large walkway named the Amic Deck was constructed across the De Villiers Graaff Motorway which bisects the campus, linking East Campus with West Campus.[1]

The 1980s also witnessed a period of heightened opposition to apartheid, as the university struggled to maintain its autonomy in the face of attacks from the apartheid state. Wits looked anew to the “Open Universities” statement of 1957, to which the University of the Western Cape now also added its voice. As the apartheid government attempted, through the threat of financial sanctions, to bring Wits under firmer control, protest escalated culminating in the General Assembly of 28 October 1987, at which the university reiterated its commitment to the values underlying the “Open Universities” statement.[15]

University management itself came under increasing grassroots pressure to implement change within the university. A Wits-initiated research project, Perspectives of Wits (POW), published in 1986, revealed a surprising disconnect between the perceptions disadvantaged communities had of Wits and the image Wits had been attempting to convey of itself as a progressive opponent of apartheid. POW, which had involved interviews with members of organisations among disadvantaged communities in the PWV area, international academics, students and staff at Wits, and even a meeting with the then-banned ANC in Lusaka, revealed that to many in the surrounding disadvantaged communities, there was a perception of Wits as an elitist institution dominated by white interests. A need was identified for further transformation of the university.[15]

However, instead of translating POW’s proposals into institutional plans for transformation, Wits reacted in a defensive manner and refused to even acknowledge many of the criticisms that had been raised. Within the university community the perception was different—it was felt that Wits was on the right track. The contradiction between internal and external perceptions would increasingly undermine the unity of the university community, as progressive elements on campus began to take more radical positions in opposition to apartheid. Internal debates about, among other things, the international academic boycott of South Africa and the role of academics in the anti-apartheid struggle led to increasing division within the university. University management was increasingly seen as isolated and out of touch, and began to be referred to by the metonym “the eleventh floor”, referring to the eleventh floor of Senate House where top management at Wits is located.[15]

Nonetheless, the university community in general continued to uphold its opposition to apartheid and its commitment to university autonomy and academic freedom. The remainder of the 1980s saw numerous protests on campus, which often ended with police invasions of the university. In 1990, when Nelson Mandela was released, the students of Men’s Res, on East Campus, unofficially renamed the lawn outside their residence “Mandela Square”.

The Science Stadium, on West Campus, completed in 2012.

In 2012 Wits celebrated the ninetieth anniversary of its upgrade to university status.

Post-apartheid: 1994–present[edit]

On 25 February 2000, university management began implementing a policy called “Wits 2001” under which work deemed ‘non-core’ to the functioning of the university (such as cleaning and landscaping) was outsourced to external contractors; the university’s academic departments were also restructured: the university’s nine faculties were reduced to five, the university’s 99 departments were merged into 40 schools, and courses that were deemed redundant following a mass review were cancelled.[17][18] Wits management did, however, initiate programmes to ameliorate some of the negative effects of Wits 2001. These included the implementation of early retirement and voluntary severance packages to minimise retrenchments. Additionally, many of the affected employees’ children were studying at Wits at the time, and received bursaries as part of their parents’ employment contracts with Wits. The university therefore continued to offer bursaries to them until the completion of the degrees for which they were then enrolled, as well as offering bursaries to the children of affected employees who matriculated in 2000.[19][20]

Wits 2001 attracted widespread criticism from the workers and staff affected, as well as from students and other staff. The arguments behind the restructuring were criticised as badly reasoned, and the policy itself was criticised as being regressive and neoliberal.[21][22] The then-vice-chancellor, Professor Colin Bundy, said in defence of Wits 2001 that “[t]his fundamental reorganisation of both academic activities and support services will equip the university for the challenges of higher education in the 21st Century”.[19] Management issued a statement on 30 May 2000 responding to criticism of Wits 2001 from the National Education, Health and Allied Workers’ Union (NEHAWU), the largest trade union among Wits employees, in which it defended Wits 2001 as constituting the “outsourcing [of] contracts for certain non-core functions, rather than any shift in ownership relations or governance” contra NEHAWU’s claims that it constituted privatisation. Management further defended the changes as “improving the financial sustainability of Wits, taking pressure off management and students, and allowing for better academic and support facilities and services”.[23] Along with “Igoli 2002” in Johannesburg, Wits 2001 was one of the policies implemented in the early 2000s which resulted in the formation of the Anti-Privatisation Forum (APF).

In 2002, the Johannesburg College of Education was incorporated into the university as Wits Education Campus under the national Department of Education’s plan to reform tertiary education in South Africa.[16] In 2003, a student mall, called the Matrix, was opened in the Student Union Building on East Campus.[24]

Coat of arms[edit]

The current coat of arms of the university was designed by Professor G. E. Pearse, and edited by Professor W. D. Howie to correct heraldic inaccuracies, before being accepted by the State Herald of South Africa in 1972. The design of the coat of arms incorporates a gold background in the upper section of the shield to represent the Witwatersrand gold fields – on which the mining industry that gave rise to the university is based – along with an open book superimposed upon a cogwheel, representing knowledge and industry. The silver wavy bars on the lower section of the shield represent the Vaal and Limpopo rivers which form the northern and southern borders of the Witwatersrand gold fields. Above the shield is the head of a Kudu, an antelope typical of the Witwatersrand and the university’s mascot. The university’s motto, “Scientia et Labore“, meaning “Through Knowledge and Work” in Latin, appears just below the shield.[25]

The badge of the South African School of Mines

The university’s coat of arms evolved from the badge of the South African School of Mines. This badge consisted of a diamond with a shield superimposed upon it. A prospector’s pick and a sledge hammer overlaid with broken ore and a mill appeared on the shield. The South African School of Mine’s motto was the same as the university’s current one, and surrounded the shield.[25]

Governance and administration[edit]

Solomon Mahlangu House, on East Campus, is home to the University’s Senate, Council, and management.

East Campus as viewed from the SRC offices in the Student Union Building.

The Great Hall facade is a provincial heritage site.

As set out in the Higher Education Act (Act No. 101 of 1997)[26] and in the Statute of the University of the Witwatersrand,[27] the university is governed by Council. The Chancellor of the university is the ceremonial head of the University who, in the name of the university, confers all degrees. The positions of Principal and Vice-Chancellor are merged, with the Vice-Chancellor responsible for the day-to-day running of the university and accountable to Council. Council is responsible for the selection of all Vice-Chancellors, Deputy Vice-Chancellors and Deans of Faculty.[27]

The responsibility for regulating all teaching, research and academic functions of the university falls on Senate. Additionally, the interests of the university’s students are represented by the Students’ Representative Council (SRC), which also selects representatives to Senate and Council.[27]

Campuses[edit]

The university is divided into five academic campuses. The main administrative campus is East Campus. Across the De Villiers Graaff Motorwaylies West Campus. The two are joined by a brick-paved walkway across the highway called the Amic Deck. East and West Campus effectively form a single campus, bordered by Empire Road to the north, Jan Smuts Avenue to the east, Jorrissen Street and Enoch Sontonga Road to the south and Annet Road to the west. The historic East Campus is primarily the home of the faculties of Science and Humanities, as well as the University Council, Senate and management. West Campus houses the faculties of Engineering and the Built Environment, and Commerce, Law and Management. East Campus is home to four residences, namely Men’s Res (male), Sunnyside (female), International House (mixed) and Jubilee Hall (female).[28] West Campus is home to the Barnato and David Webster Halls and West Campus Village (all mixed).[29]

Wits has three more academic campuses, all located in Parktown. Wits Education Campus (WEC) houses the school of education, within the Faculty of Humanities. WEC boasts three female residences, forming the Highfield cluster, namely Girton, Medhurst and Reith Hall. East of WEC (across York Road), lies Wits Medical Campus which is the administration and academic centre of the Faculty of Health Sciences. West of WEC (across Victoria Avenue) lies the Wits Management Campus, with the Wits Business School. Within the Wits Management Campus are the Ernest Oppenheimer Hall (male residence) and the mixed Parktown Village.

There are centres that are not academic although referred to by the university as campuses. These are Graduate Lodge, Campus Lodge, South Court and Braamfontein Centre; all in the city district of Braamfontein and all mixed gender. Furthermore, there is the Wits Junction (mixed) and the Knockando Halls of Residence (a male residence located on the grounds of a Parktown mansion called Northwards) in Parktown, and the mixed Esselen Street Residence in Hillbrow.

Sites[edit]

Provincial heritage sites and heritage objects[edit]

The University of the Witwatersrand houses two provincial heritage sites and two heritage objects. The Great Hall (technically the façade of Central Block in which the Great Hall is located),[30] and the Dias Cross housed in the William Cullen Library[31] are both provincial heritage sites. They were formerly national monuments, until 1 April 2000 when the National Monuments Council was replaced by a new system which made former national monuments the responsibility of provincial governments following the passage of the National Heritage Resources Act.[32] The heritage objects are Jan Smuts’ study, housed in Jan Smuts House,[33] and the Paul Loewenstein Collection of rock art.[34] All of the university’s national heritage sites and objects are located on East Campus.

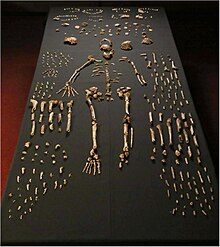

Homo naledi, discovered by a Wits-based team of palaeontologists working in the Cradle of Humankind.

Wits Institute of Social and Economic Research (WiSER)[edit]

The University of the Witwatersrand is home the Wits Institute of Social and Economic Research (WiSER), founded in 2001 by Deborah Posel. The institute has brought renowned speakers, both domestic and international, to deliver thought-provoking conversations around interdisciplinary research as well as award-winning novelists, Fiston Mwanza Mujila, French author of Tram83, who make use the buildings seminar room. No stranger to its own success, WiSER fosters the countries top, acclaimed academics like Achille Mbembe, who won the prestigious Geschwister-Scholl-Preis -German book prize- in 2015.[35] The University’s faculty of Humanities continues to be a partner to WiSER, pathing the way to the cultivation of intellect in both the university and in the wider community. [36]

Cradle of Humankind[edit]

Wits acquired the Sterkfontein and Swartkrans sites in the 1960s, both of which were rich in fossil remains of early hominids.[1] In 1999, the area was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO as the Cradle of Humankind. As a World Heritage Site, responsibility for the site shifted from the university to the government of Gauteng Province, with the provincial government becoming the designated management authority responsible for developing and protecting the site. It is aided by the South African Heritage Resources Agency, which has also declared the area a national heritage site.[37] The University’s archaeology and palaeontology departments, within the School of Geosciences of the Faculty of Science, continue to play a leading part in excavations of the site; and Wits retains ownership of Sterkfontein’s intellectual rights.[38] Professor Lee Berger discovered Australopithecus sediba(2010) and Homo naledi (2015) at the site.[39][40]

Museums[edit]

The Origins Centre museum from across the M1.

The university hosts at least fourteen museums. These include the Adler Museum of Medicine, the Palaeontology Museum and the only Geology Museum in Gauteng Province. The displays include a vast spectra not limited to the Taung skull, various dinosaur fossils and butterflies.

Rock art[edit]

The Roberts-Pager Collection of Khoisan rock art copies is located in the Van Riet Lowe building on East Campus.

Johannesburg Planetarium[edit]

The Johannesburg Planetarium was the first full-sized planetarium in Africa and the second in the Southern Hemisphere. It was originally bought by the Johannesburg municipality to be set up as part of the celebration of the city’s seventieth anniversary. After acquiring an old projector from the Hamburg Planetarium, which was modernised before being shipped to South Africa, the municipality sold the projector to the university for use as both an academic facility for the instruction of students, and as a public amenity. Plans for a new building to house the projector were first drawn up in 1958, and construction began in 1959. The planetarium finally opened on 12 October 1960.[41] The Johannesburg Planetarium is often consulted by the media, and the public, in order to explain unusual occurrences in the skies over South Africa.[42][43] In 2010, the Johannesburg Planetarium celebrated its golden jubilee.[44]

Wits Art Museum[edit]

The museum’s collection started in the 1950s and has since grown substantially.[45] In 1972 the Gertrude Posel Gallery was established on the ground floor of Senate House on East Campus. It was joined in 1992 by the Studio Gallery which formed the “lower gallery” reserved for the display of African art. The galleries’ collections grew steadily, with the Studio Gallery becoming renowned for having one of the best collections of African beadwork in the world, and by 2002 it was decided that more space was needed. Thus, the Gertrude Posel Gallery and the Studio Galley were closed. The ground floor of University Corner was selected as the site for the new Wits Art Museum, which now houses the collections after it was completed and launched in 2012.[46]

Wits Theatre[edit]

The Wits Theatre is a performing arts complex within the university, although it also caters for professional companies, dance studios and schools.[47] It is run by the university’s Performing Arts Administration (PAA).[48] Prior to the opening of the Wits Theatre, the Wits Schools of Dramatic Art and Music had been staging productions in a building on campus called the Nunnery, a former convent. The Nunnery has been retained as a teaching venue.[49]

Academics[edit]

Research[edit]

Wits University is the home to 28 prestigious South African Research Initiative (SARChI) Chairs and six DST-NRF Centres of Excellence. There are just more than 411 NRF rated researchers, of which 26 are ‘international leading scholars’ in their research fields, or so called A-rated researchers. The University also has a wide range of research entities including 14 large externally funded research institutions.[50]

Graduation ceremony: vice chancellor Adam Habib capping a Ph.Dgraduate

Faculties[edit]

The university consists of five faculties: Commerce,Law and Management, Engineering and the Built Environment, Health Sciences, Humanitiesand Science.

Commerce, Law, and Management[edit]

This Faculty currently offers various undergraduate and postgraduate degrees in accountancy, economics, management, and law. It boasts the acclaimed Wits Business School, as well as a graduate school devoted to public and development management. The faculty participates in the WitsPlus programme, a part-time programme for students, and is based in the Commerce, Law and Management Building on West Campus.

Engineering and the Built Environment[edit]

This Faculty is made up of 7 schools being: Architecture & Planning, Chemical and Metallurgical Engineering, Civil & Environmental Engineering, Construction Economics & Management, Electrical & Information Engineering, Mechanical, Industrial & Aeronautical Engineering and Mining Engineering. The faculty is based in the Chamber Of Mines Building on West Campus, which houses the faculty office and the Engineering Library. The School of Civil & Environmental Engineering and Chemical and Metallurgical Engineering are located in the Hillman and Richard Ward Buildings on the East Campus respectively.

Health Sciences[edit]

This Faculty is based on the Wits Medical Campus in Parktown. This Faculty uses the Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital, the Charlotte Maxeke Hospital, the Helen Joseph Hospital, and the Rahima Moosa Mother and Child Hospital as its teaching hospitals. The Dean of the Faculty is Professor Martin Veller.[51][52] The faculty offers undergraduate degrees in dentistry, medicine, medical and health sciences, nursing, occupational therapy, physiotherapy and pharmacy. It also runs a graduate entry medical programme, masters courses (science and medicine) and a PhD programme.

Humanities[edit]

This Faculty is based in the South West Engineering Building on East Campus[53] and consists of the schools of Social Sciences, Literature and Language Studies, Human and Community Development, Arts, and Education.[54]

Science[edit]

The Faculty is based in the Mathematical Sciences Building within the Wits Science Stadium on Braamfontein Campus West and consists of the schools of Animal, Plant and Environmental Sciences; Chemistry; Physics; Molecular and Cell Biology; Geography, Archaeology and Environmental Studies; Geosciences; Mathematics; Statistics and Actuarial Science and School of Computer Science and Applied Mathematics.[55]

Libraries[edit]

The Wartenweiler Library, on the south-eastern side of the Library Lawns on East Campus.

The William Cullen Library, on the north-western side of the Library Lawns on East Campus.

The University of the Witwatersrand Library Service consists of two main libraries, the Warteinweiler and William Cullen libraries on East Campus,[56] and twelve branch libraries. The Wartenweiler Library primarily serves the Faculty of Humanities. It also contains the Library Administration, Library Computer Services and Technical Services departments as well as the Short Loan collection, the Reference collection, Inter-library Loans department, the Multimedia Library, and the Education and Training department as well as the Electronic Classroom.[57] The William Cullen Library contains the Africana collection, specialising in social, political and economic history. It also contains the Early and Fine Printed Books collection, which includes the Incunabula (books printed before 1501). Finally, it also contains a collection of Government Publications and journals in the arts, humanities and social sciences.[58] The branch libraries are:

- The Martienssen Library For The Built Environment, which serves the schools of architecture and planning and construction management within the Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment. It is located in the John Moffat Building (also known as the Architecture Building) on East Campus.[59]

- The Biological & Physical Sciences Library which is situated in the Oppenheimer Life Sciences Building on East Campus and serves the Faculty of Science, together with the Geomaths Library.[60]

- The Commerce Library which, along with the Wits Library of Management, serves the schools of commerce and management. It is located to the west of the Tower of Light on West Campus.[61]

- The Education Library (also known as the Harold Holmes Library) which is located on Wits Education Campus in Parktown and serves the school of education within the Faculty of Humanities.[62]

- The Engineering Library, which is located in the Chamber of Mines Building on West Campus and serves the schools of engineering within the Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment.[63]

- The GeoMaths Library, which is situated in the basement of Senate House on East Campus and serves a range of schools within the faculties of Science, Engineering and the Built Environment, and Humanities.[64]

- The Witwatersrand Health Sciences Library (WHSL) which serves the Faculty of Health Sciences. It is divided into four branches, one of which (formerly at Helen Joseph Hospital) is now a “virtual library” available only online. Two of the other branches are at the Wits Medical Campus in Parktown, while the remaining branch is at the Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital in Soweto.[65]

- The Wits Library of Management, which, together with the Commerce Library, serves the schools of commerce and management. It is located in the Donald Gordon Building on the Management Campus in Parktown.[66]

- The Law Library which serves the school of law within the Faculty of Commerce, Law and Management. It is located in the Oliver Schreiner Law Building on West Campus. Unlike the University’s other libraries, the Law Library is governed directly by the school of law, rather than by the University of the Witwatersrand Library.[67]

The Library also manages the university institutional repository (WireDspace (Wits Institutional Repository on Dspace – http://wiredspace.wits.ac.za)

Reputation and ranking[edit]

The Student Union Building on East Campus.

A pond by the Gavin Reilly Green on West Campus.

Wits University was ranked as the top university in South Africa and 176th in the world in the Center for World University Rankings (CWUR) in 2016.[68] Wits has held the position of top university in South Africa, according to the CWUR rankings, since 2014.

The 2009 Times Higher Education-QS World University Rankings ranked Wits as 250–275 in the world.[69] In 2013, Times Higher Education-QS World University Rankings ranked Wits again as 226–250 in the world, an improvement on the 2009 ranking.[70]

In its capacity as a business school, the University of Witwatersrand was placed as the 6th best business school in Africa and the Middle East in the 2010 QS Global 200 Business Schools Report.[71] As well as being voted the best MBA in South Africa by the Financial Mail 6 years running.

Frankenwald controversy[edit]

The John Moffat Building on East Campus.

West Campus Village, a student residence located to the west of the Gavin Reilly Green.

Gatehouse, on East Campus, houses the Faculty of Science.

In 1905 the mining magnate Alfred Beit donated a large piece of land, Frankenwald Estate, north of Johannesburg, to the Transvaal Colony to be used for ‘educational purposes’ – the land was transferred to Wits in 1922 by an Act of Parliament. According to the Mail & Guardian the University entered into an agreement in 2001 with a private developer, iProp, to build a shopping centre, offices, light industry and medium and high-density housing on the property.[72]

Student demographics[edit]

The removal of the legacy of apartheid is generally considered an important matter in South African socio-political and academic discourse. As such, the University of the Witwatersrand maintains an admission policy that actively seeks to create diversity within the university’s student population and bring it in line with the country’s demographics, while nonetheless attempting to balance such goals with academic success.[73]

Racial composition[edit]

The racial composition of the university’s student population is as follows:[7]

| Racial composition, 2017 | Percentage | Total number |

|---|---|---|

| Black | 56,33% | 21 604 |

| White | 17.51% | 6 716 |

| Indian | 12.10% | 4 639 |

| Coloured | 3.88% | 1 489 |

| Chinese | 0.40% | 152 |

| Undisclosed | 0.00% | 1 |

| Total | 100% | 38 353 |

Gender composition[edit]

The gender composition of the university’s student population is as follows:[7]

| Gender composition, 2017 | Percentage | Total number |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 54.86% | 21 034 |

| Male | 45.12% | 17 300 |

| Total | 100% | 38 343 |

Notable alumni and academics[edit]

Nobel Prize Laureates[edit]

- Aaron Klug, 1982 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

- Nadine Gordimer, 1991 Nobel Prize in Literature

- Nelson Mandela, who attended but did not graduate from the university, 1993 Nobel Peace Prize

- Sydney Brenner, 2002 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

See also[edit]

- Dawn of Humanity (2015 PBS film)

- Widdringtonia whytei

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m Wits University Archived 12 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine., History of Wits, retrieved 13 December 2011

- ^ Jump up to:a b Wits University Archived 27 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine., Short History of the University, retrieved 26 February 2015

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e [1], University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg FACTS & FIGURES 2017/2018, retrieved 4 August 2018

- ^ University World News, SOUTH AFRICA: New university clusters emerge, retrieved 13 December 2011

- ^ University of Cape Town Archived 25 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine., Welcome to UCT, retrieved 13 December 2011

- ^ Stellenbosch University Archived 31 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine., Historical Background, retrieved 13 December 2011

- ^ Jump up to:a b c [2], Wits Facts & Figures 2017 / 2018, retrieved 2 November 2018

- ^ University of Pretoria Archived 16 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine., Historic Overview, retrieved 26 May 2010

- ^ South African History Online, “Wits attains full university status”, retrieved 7 December 2011

- ^ Munro, K. 2008. Hofmeyr House – from Principal’s residence to heritage staff club. Wits Review, pp. 29

- ^ South African History Online, “The inauguration of the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) is celebrated”, retrieved 13 December 2011

- ^ Alan Paton, Hofmeyr, 1964, p.81

- ^ South African History Online, “Wits attains full University status”, retrieved 13 December 2011

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Wits University (web archive), 75 momentous years…a snapshot of the University of the Witwatersrand (archived in 1998), retrieved 30 December 2011

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f The Institutional Context of Restructuring External and Internal Determinants, retrieved 13 December 2011

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Joburg.org.za Archived 6 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine., “Wits turns 85 today”, retrieved 30 December 2011

- ^ “Neo-liberalism has come to the University of the Witwatersrand through retrenchments, commercialisation, and privatisation”, Lucien van der Walt, 2000, retrieved 13 December 2011

- ^ Wits University (web archive), “Wits 2001 Academic Restructuring and Support Services Review: Keeping staff informed” (8 February 2000), retrieved 29 December 2011

- ^ Jump up to:a b Wits University (web archive), “Wits Council approves major changes” (26 February 2000), retrieved 29 December 2011

- ^ Wits University (web archive), “Wits Council reiterates support for restructuring plans” (3 June 2000), retrieved 29 December 2011

- ^ Crisis of Inequality at Wits (South Africa) by Kezia Lewins, retrieved 13 December 2011

- ^ Neo-liberalism has come to the University of the Witwatersrand through retrenchments, commercialisation, and privatisation, Lucien van der Walt, 2000, retrieved 13 December 2011

- ^ Wits University (web archive), “Wits Refutes NEHAWU Claims” (30 May 2000), retrieved 29 December 2011

- ^ Wits University Archived 27 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine., Short history of the University, retrieved 13 December 2011

- ^ Jump up to:a b Wits University, Coat of Arms, retrieved 1 January 2012

- ^ Higher Education Act (Act No, 101 of 1997)

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Statute of the University of the Witwatersrand

- ^ Wits University Archived 5 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine., East Campus Cluster of Residences, retrieved 13 December 2011

- ^ Wits University Archived 5 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine., West Campus Cluster of Residences, retrieved 13 December 2011

- ^ South African Heritage Resources Agency, Gazetted Items, Central Block of Wits University, retrieved 1 January 2012

- ^ South African Heritage Resources Agency, Gazetted Items Archived 26 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine., Dias Cross at Wits University, retrieved 1 January 2012

- ^ South African Heritage Resources Agency, Introduction, retrieved 1 January 2012

- ^ South African Heritage Resources Agency, Gazetted Items, Jan Smuts’ Study at Wits University, retrieved 1 January 2012

- ^ South African Heritage Resources Agency, Paul Loewenstein Collection at Wits University, retrieved 1 January 2012

- ^ The African Courier. 2015. Cameroonian Achille Mbembe wins German book prize. Retrieved October 13, 2017 from the World Wide Web: http://www.geschwister-scholl-preis.de/preistraeger_2010-2019/2015/index.php

- ^ The University of the Witwatersrand. 2017. Faculty of Humanities. Retrieved October 13, 2017 from the World Wide Web: https://www.wits.ac.za/humanities/

- ^ Maropeng, About Maropeng, retrieved 1 January 2012

- ^ Wits University Archived 26 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine., Places of Interest, Arts and Culture, retrieved 1 January 2012

- ^ Berger, L. R.; de Ruiter, D. J.; Churchill, S. E.; Schmid, P.; Carlson, K. J.; Dirks, P. H. G. M.; Kibii, J. M. (2010). “Australopithecus sediba: a new species of Homo-like australopith from South Africa”. Science. 328 (5975): 195–204. doi:10.1126/science.1184944. PMID 20378811.

- ^ Berger, Lee R.; et al. (10 September 2015). “Homo naledi, a new species of the genus Homo from the Dinaledi Chamber, South Africa”. eLife. 4. doi:10.7554/eLife.09560. PMC 4559886. PMID 26354291. Retrieved 10 September 2015. Lay summary.

- ^ Johannesburg Planetarium, retrieved 1 January 2012

- ^ Mail & Guardian Online, “Sun halo piques South Africans’ interest”, retrieved 1 January 2012

- ^ Mail & Guardian Online, “Bright light over Johannesburg: Meteor or prawns?”, retrieved 1 January 2012

- ^ Mail & Guardian Online, “Jo’burg planetarium celebrates”, retrieved 1 January 2012

- ^ “Our History | About Us | Wits Art Museum | Places and Spaces – Wits University”. www.wits.ac.za. Retrieved 2015-05-19.

- ^ Wits Art Museum, Our History, retrieved 1 January 2012

- ^ Wits University, Wits Theatre, retrieved 1 January 2012

- ^ Wits University, Wits Theatre, About Us, retrieved 1 January 2012

- ^ Wits University, Wits Theatre, About Us, History, retrieved 1 January 2012

- ^ Wits University, Research highlights, retrieved 12 June 2017

- ^ Wits University, Faculty of Health Sciences, retrieved 1 January 2012

- ^ Wits University Faculty of Health Sciences, Contact Us, retrieved 1 January 2012

- ^ “Archived copy”. Archived from the original on 4 December 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- ^ http://www.wits.ac.za/humanities

- ^ http://www.wits.ac.za/science

- ^ Wits University Library, “About Us”, retrieved 13 December 2011

- ^ Wits University Library, Wartenweiler Library, retrieved 13 December 2011

- ^ Wits University Library, William Cullen Library, retrieved 13 December 2011

- ^ Wits University Library, Architecture Library, retrieved 13 December 2011

- ^ Wits University Library, Biophy Library, retrieved 13 December 2011

- ^ Wits University Library, Commerce Library, retrieved 13 December 2011

- ^ Wits University Library, Education Library, retrieved 13 December 2011

- ^ Wits University Library, Engineering Library, retrieved 13 December 2011

- ^ Wits University Library, Geomaths Library, retrieved 13 December 2011

- ^ Wits University Library, WHSL, retrieved 13 December 2011

- ^ Wits University Library, Wits Library of Management, retrieved 13 December 2011

- ^ Wits University Library, Law Library, retrieved 13 December 2011

- ^ “CWUR 2016 | Top Universities in South Africa”. cwur.org. Retrieved 2016-07-22.

- ^ “University of the Witwatersrand”. Top Universities. QS Quacquarelli Symonds. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- ^ “University of the Witwatersrand”. Top Universities. Times Higher Education. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- ^ Top MBA.com, Global 200 Top Business Schools 2010 by Region: Africa and Middle East, retrieved 1 January 2012

- ^ http://mg.co.za/article/2011-03-18-wits-embroiled-in-land-dispute

- ^ Wits University, Admissions Policy, retrieved 1 January 2012

Bibliography[edit]

- The Golden Jubilee of the University of the Witwatersrand 1972 ISBN 0-85494-188-6 (Jubilee Committee, University of the Witwatersrand Press)

- Wits: The Early Years : a History of the University of the Witwatersrand Johannesburg and its Precursors 1896 – 1936 1982 Bruce Murray ISBN 0-85494-709-4 (University of the Witwatersrand Press)

- Wits Sport: An Illustrated History of Sport at the University of the Witwatersrand 1989 Jonty Winch ISBN 0-620-13806-8 (Windsor)

- Wits: A University in the Apartheid Era by Mervyn Shear (1996) ISBN 1-86814-302-3 (University of the Witwatersrand Press)

- Wits: The “Open Years”: A History of the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, 1939–1959 1997 Bruce Murray ISBN 1-86814-314-7 (University of the Witwatersrand Press)

- A Vice-Chancellor Remembers: the Memoirs of Professor G.R. Bozzoli 1995 Guerino Bozzoli ISBN 0-620-19369-7 (Alphaprint)

- Wits Library: a Centenary History 1998 Reuben Musiker & Naomi Musiker ISBN 0-620-22754-0 (Scarecrow Books)